|

After getting back to Kyoto late at night, I didn’t have a whole lot of time before things closed. I swiftly changed into a pair of jeans and a fresh t-shirt and started walking around. I initially tried to catch the Kyoto Imperial Palace, but regrettably, it closed just before I got there. The pictures below are all I saw of it.... (follow the link)

4 Comments

He was gaining on me and we were running out of space. One could argue I knew what would happen when I beat him in groundwork earlier in practice, but as humans, we tend to sacrifice long term gains for short term victories.

Part of Four Days in London: A memoir about trying to find a way to the Olympics, and finding something else instead. This set of stories take place in late January and continued until March 2010.

The Move in I finished packing my stuff. It was my last day after a little over a week in the athletes dorm. My friend Taka had told me to bring my things to dojo that night and I would find out who I was living with. At the beginning of practice the coach asked the group who might have space. Several people volunteered, and he chose a man I’d get to know as Sawano... I didn’t have a hard time biking to the train station. It was only a few miles from the university. On my way I passed by a giant rocket that was in the center of town. I noted the landmark for future path finding purposes, not anticipating I would have difficulty spotting it from the train station. Confident in how simple it seemed to be to get to the station, I didn’t bother to grab a map or directions back to the university...

It is four AM and everything is quiet. I am in a common area for the athletes dorm. There’s a television I haven’t bothered to turn on. I browse the web on my phone and make a phone call home. It won’t be a long conversation, after all it is an international call, but it helps me pass the time. I walk back over to the room I’m staying. Of all the things I wish I had pictures of, the intercoms I pass by are high on the list. The have red dots and look almost exactly like Hal from 2001 a Space Odyssey.

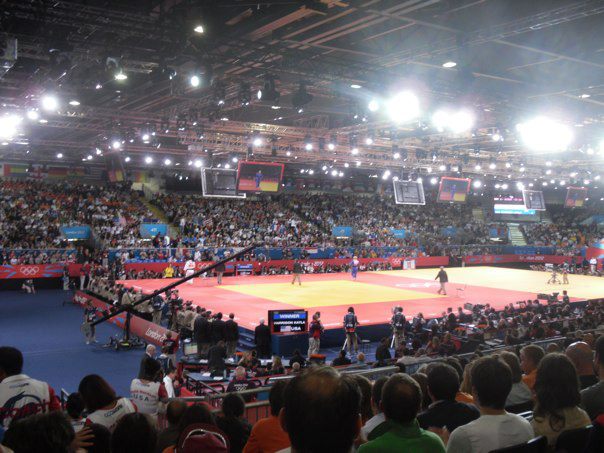

Continued here... ”Why did you want to climb Mount Everest?” “Because it’s there” George Mallory responding to a journalist “Great ambition and conquest without contribution is without significance.” Ethan Canin Mat side at the London Olympic Games When I was in the 7th grade my science teacher had a poster. The poster read “Shoot for the moon because even if you miss you will land among the stars.” Despite being corny and scientifically dubious when taken at face value the poster had a valid point about goal setting. That poster is an accurate description of my life events up to this point. I think I’ve spent the last five years processing and coming to understand the five years that preceded it. As part of processing these events, I want to tell you a story. This is a story about how in those first five years a mildly autistic kid from New England attempted the most difficult challenge in American martial arts: qualifying for the Olympic Games in the sport of judo. While tae kwon do and boxing carry with them real possibility of brain damage, and the work ethic of the wrestler is the stuff of legend, the qualification process for judo is a fascinating hell. When we compare the three Olympic martial arts, the grappling arts are empirically more difficult. This is not to take away from the incredible feats performed by Tae Kwon Do and boxing practicioners. If you’ve ever taken a round house kick or a right hook to the jaw and kept moving forward, you are something special. The fact is that neither of these carry with them the same energy expenditure, and the constant threat of joint damage, that grappling sports have. Just ask your friendly neighborhood MMA fighters which they find more tiring if you don’t believe me. Team FORCE before the 2008 Olympic Trials The only thing that makes the qualification process for judo more difficult than the process for wrestling has three syllables: scholarships. A young wrestler can receive an athletic scholarship, guaranteeing them an education. Wrestling in college is an expectation for those on the path to Olympic glory. While the NCAA system is in desperate need of reform, at least when a wrestler ends his thankless college career, which carried with it no possibility of million dollar contracts and a tiny fan base, they have a bachelors degree. They have a pathway to make money for their family. The United States sent five people to the 2012 Olympic Games. Only one had finished their undergraduate degree. It is likely they all carried with them thousands of dollars in debt. While judo finally began paying cash prizes at the highest levels, this money is not a guaranteed salary for a starving athlete. The demanding international competition schedule makes the standard brick and mortar undergraduate education almost impossible. There exists only three high level collegiate judo programs, with only one readily equipped as of this writing to produce Olympic medals. On the fourth day of competition in London, I called a friend who had competed in the Olympics in the past. This friend, a successful businessman with a doctorate, who would be the first tell you that an appearance at the Olympics could cost you more than you could ever pay back. Yet when I explained how despite knowing how bad a decision it would be to pursue the Olympics again, that I couldn’t help but want to go through all the pain again just for a chance, however small, that I’d make it, he responded in a voice just above a whisper: “Because you’ve seen it.” This is a story about how I tried to make the Olympic team, and the impact it had on my life. I promise, the story isn’t all gloom. In fact thanks to my family and some very smart friends, I was one of the lucky ones who despite not making it came out ahead. While there are ups and downs to this story, these were some of the best years of my young life. With friends at the 2012 Olympic Games This project is ongoing. While I have a rough outline below, I expect it will take some time to complete. My hope is to release a section a week until it is finished. If it isn’t hyperlinked, the section isn’t available yet. In general my intention is to follow the order below. As such I will be updating this post every week as new content is uploaded. Names have been changed through out the story where I’ve felt it necessary.

Chapters Part 1 Ticket to Tokyo Part 1 Ticket to Tokyo Part 2 Kangeiko How to hold a pencil The Kodokan Don’t trust the Nigerian Mafia Kyoto Coming Home How to eat an artichoke National Championships Part 2 In Transit Stories Part 1 Travis Scotland Merrimack Belize Collegiate Nationals Nick One Final Push The Email Part 3 In Transit Stories Part 2 The Announcement Ronda Athens Indianapolis Lowell Beijing Kyle US Open Part 4 2011 International Animal Behavior Society Chaos ensues Coming to terms Kayla Signing on the dotted line San Jose Marti One last try Preparing for London Ticket to London Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Ending an Athletic Career as an Athlete on the Spectrum Fossil fuel divestment has been charged largely as a moral movement. Depending on your point of view, this is absolutely true. Divestment alongside the Keystone XL pipeline have become rallying cries for the environmental movement, generating substantial political capital. When this new found political capital is combined with favorable economics, you begin to see regulatory action like Obamas’ Clean Power Plan. While I am primarily concerned with tackling climate change, my interest in divestment in higher education is much more down to earth. Worldwide financial markets carry a dangerous carbon bubble, and this threatens the endowments of institutions I cherish.

Merrimack College is a small liberal arts school in Massachusetts. It prides itself on providing a well-rounded education, excellent training for STEM students, and provided a place for me to grow up. My parents both graduated from Merrimack, they even got married there. My mother worked there on and off for over a decade. Its’ there I completed my B.S. in biology, where is I met many good friends. I had professors who had my parents, and it that brought me a small sense of joy. Fossil fuel companies represent a major bubble in the existing financial markets. We’ve already begun to see what such a financial bubble may look like with coal companies. The total market value of publicly-traded U.S. coal companies between April 2011 and April 2014 dropped 63%. While this is largely attributable to the expansion of shale gas, it may be a general warning sign. The expansion of shale gas and subsequent drop in price has provided the political cover necessary for coal plants to be targeted for a new set of regulations (the Clean Power Plan). Renewables are getting ever closer to price parity with natural gas (granted with subsidies), and when that begins to happen we may begin to see natural gas give way as well. Small colleges across the United States are closing their doors; which is hardly news. As my generation faces down their school loans, our younger members are moving away from costly small private colleges. Still the classic American liberal arts education helps to develop well rounded citizens. While I certainly felt a little bored my senior year being at a small school, I knew from experience at UMass Lowell that I go the attention I needed at a smaller school. I’m not even religious, and I thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to discuss organic chemistry and theology in the same day. According to Carbon Tracker fossil fuel companies carry stranded assets. Fossil fuel companies are valued with the assumption they will sell all of their product (oil, gas, etc). Regulatory action such as an agreement at the 2015 Paris talks that restricts CO2 emissions would inevitably require these companies not to sell all of their product. Thus if humanity takes serious action on climate change, barring a technological stop-gap, fossil fuel companies will lose their value. The potential for a rapid devaluation of fossil fuel companies creates financial risk. In my graduate work I’ve attended schools whose endowments that I’m sure could take a blow from the perceived carbon bubble. Harvard has an endowment around 31 billion dollars. I do not know the details of the endowment for Indiana University, but it is a large university system that I assume could withstand the shock. I imagine the UMass system is in a similar position. Likewise I don’t know how the endowment is doing over at Merrimack. I do know that it’s a great school that I’m very happy I attended. I hope they’re doing their homework. I don’t do very much judo anymore. The truth is my body has a difficult time holding up when I do it, and to come back to it on a full time basis would require some significant rehab. While the possibility still exists to return to serious judo competition later on, at this time I’m content focusing on Brazilian jiujitsu. One of the reasons I'm content with bjj is that it includes something missing in judo: leg grabs. This isn’t news, as the ban on leg takedowns has been in place since January 2013, and a variation since 2010. While many people were excited about the rule change, most have frowned upon the removal of an entire area of expertise from judo. A generation of judoka are coming up that do not have to worry about a double leg. There is a serious cost to this aesthetic choice by the IJF.

The first cost is from a martial arts perspective. It's quite simple: if I don’t train to deal with a technique, there is no guarantee that if it's used on me I will know how to react. My reactions to wrestling style takedowns have dramatically deteriorated. I didn’t realize this till I went to a Brazilian jiujitsu workout and had the opportunity to train with Renan Borges. Renan is an accomplished Brazilian jiujitsu blackbelt. After being introduced as a nationally ranked judoka and a training partner for members of the US Olympic team, you can imagine my embarrassment when Renan nailed me with a low single leg takedown out the gate. (To his credit, it was a great shot) In my transition to Brazilian jiujitsu competition, I’ve had to relearn wrestling. To keep this in context I wrestled for a two time state championship team in highschool, and grew up defending wrestling style takedowns in my judo career. Just imagine how difficult it will be for a generation of pure judoka to transition to a MMA or self-defense situation against a wrestler. The second cost is paid not by the athletes new to the sport, but by athletes who have been in the sport for a long time. You have stranded skillsets. If an athlete specialized before in a powerful pickup game, they won’t have an opportunity to use it again in a competition setting. This means potentially hundreds of hours of wasted time and significant frustration. I only lost one technique in the first phase of the rule change (an off the grip firemans carry). Friends of mine lost most of their repertoire. The final cost is a little bit more abstract and will matter to differently to different people. In a sense when you think about executing a technique, there's a memory attached to it. You might have very clear memories of having used it or defending it. When a technique is accessed, at least for me all of the memories associated with that technique (both good and bad) are accessed as well. When I hit an uchimata I remember training camps in upstate New York. When I throw osoto gari, I remember one of my old coaches yelling at the top of lungs for me to attack with it. When you ban a technique, you reduce the opportunity for these memories to be accessed. Everyone will put different values to these memories, but for me they matter. I understand when a technique is banned for safety reasons, but when it is banned for sport aesthetics I wonder if the benefits outweigh the costs. I grew up in special education. I initially attended a small catholic school in my home town. Things started out well enough. There were some discipline problems, which isn’t surprising for a young boy. Eventually the teachers got everything in working order, and my mother was always available with her guitar and some volunteer hours to cover for me when a teacher needed to be appeased. About three quarters of the way through first grade though, something became apparent: I had no idea how to read.

This is ironic, since today as a grad student I do nothing but read. What had happened though was pretty simple. I needed some more attention, and a young inexperienced teacher was overwhelmed with a class of 20 plus students. After some very serious tutoring through the summer, I jumped ahead a few steps of my class. In second grade I was the first person in my class to raise my hand to read aloud, and I was excited. Things weren’t perfect though. I struggled through elementary school, and never seemed to really adapt socially. I had a few good friends (two of whom I’m happy say I still see a few times a year today) but was usually omega in the pack of young kids. After a particularly bad experience in the 4th grade, and an experiment with another private school, my parents moved me over to the public program. The decision was perfect. There’s an assumption that private schools are always better than public schools. In my own education this was not the case. I think the question requires more nuance to answer, and honestly depends on where you live and what you have access to. On the collegiate level I attended one of the prestigious public universities in the country, as well as one of the most exclusive private schools in the world; the truth is I can’t really compare them. Growing up though, for me it was the public schools that provided refuge. After an evaluation at Boston Childrens Hospital, it was revealed that I was on the autism spectrum. The public schools were ready for me. I had an IEP in hand, and my grades shot up. I stayed in special education until I graduated high school. As an undergraduate and a graduate student, to compensate with issues surrounding my ability to physically write, I’ve been typically granted the chance to type on exams and when that’s not available: extra time. This was the same central accommodation I got from the seventh grade all through high school. Throughout all of this, I really disliked the word special. I don’t care when it’s used to describe situation with some nuance, or as a positive description. I’ve minded how references to special education could be used as a pejorative by people who don't understand it. Much in the same way the word retarded has been used. In the spirit of full disclosure, I’ve been guilty in using these words in the same way. I remember after a particularly terrible round of teasing in coming home and asking my mother if I was mentally retarded. Special education doesn’t mean that someone isn't intelligent. It simply means that the education system they are in needs to be adapted so they can take advantage of their strengths and improve their weaknesses. In my case it was a difficulty with hyperfocusing on (typically not school related) tasks and serious fine motor problems that left my hand writing in rough order. I traditionally scored well into the advanced categories on standardized tests. Several of my peers did as well. I attended Harvard University and I attend the top environmental policy program in the country. I was in and greatly benefited from special education. As congress cuts budgets, I do worry that special education programs will suffer. Special education programs can be expensive. Towns that rely on their states receiving federal education funding could suffer. My senior year of high school a local politician in my home town once described our special education system as a cancer. I feel like many people simply don't understand that it has an important purpose. Our education system isn't perfect, and often times adjustments are necessary to benefit different styles of learning. Whether these adjustments are made to help someone simply get through high school, or to do the things i have, they are important. This not a typical or easy topic for me to write on. While it comes up in interviews, I tend to be focused on environmental issues in my writing. It came up because I was watching Good Will Hunting. My father in his infinite ability to make me feel better brought the movie home one day. I was twelve years old and starting off in the special education program at North Andover middle school. I had felt bad about being in it. He put on the movie and at the end pointed out that the main character was smart, he just needed to be put into the right situation. That is what special education programs do: they put people in the right place so they can succeed. |

AuthorChristopher Round is a doctoral candidate at George Mason University studying information technology and climate policy. Archives

July 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed